Life on Mars

By Ian Daly, Photographs by Kevin Cooley

This article originally appeared in the November 2008 issue of Details magazine. It does a good job of capturing some of the legitimate and completely off-the-wall aspects of my time managing the Haughton-Mars Project, a NASA and Canadian government-funded research station in the Arctic.

I managed the HMP and contributed to its research program from 2005 to 2008.

ABANDON, FOR A MOMENT, YOUR CHILDHOOD FASCINATION WITH MARS and consider this unfortunate fact: It is a miserable place—lifeless, as far as we know—a frozen wasteland of rock shards and sand. The average temperature is 67 degrees below zero. Only trace amounts of oxygen hover in the near-nonexistent atmosphere, which is so thin that the cosmic radiation that reaches the surface would fry any living creature. Occasionally the Martian winds will whip themselves into hurricanes the size of Texas—or, in a calamity of such epic proportions that scientists are still at a loss to explain it, a dust storm will engulf the entire planet.

It seems reasonable, then, to regard enthusiasts like Dr. Pascal Lee, 44, a planetary geologist who's devoted much of his life to figuring out how to get to Mars, with a certain level of cynicism. And it's hard to avoid asking a decidedly un-Star Trek question: Why the hell would anyone want to go?

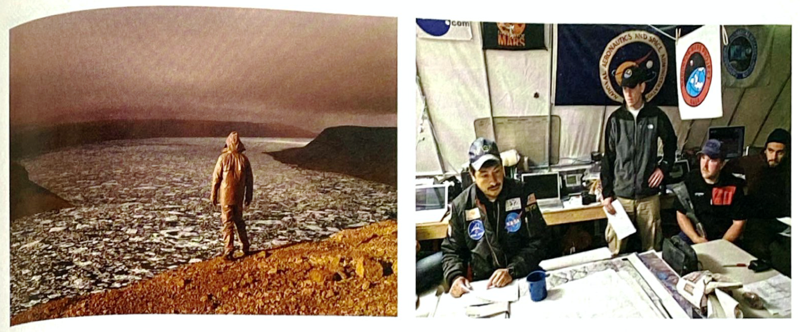

On a steel-gray afternoon in early August, Lee stands on the spine of a mountain ridge at the rim of a giant crater, a wiry Australian cattle dog named Ping Pong at his side. In every direction, an endless monochrome expanse of boulders and dust merges with the horizon. There are no signs of life anywhere—no patch of moss, no glint of a rooftop or arc of a contrail—just the vacant, ashen topography of a 12-mile wide canyon that was formed when a meteor slammed into Earth 39 million years ago. This is Devon Island—a swath of mountainous gravel a few clicks south of the magnetic North Pole. For the past 12 years, Lee and a small cadre of scientists, engineers, authors, and dreamers have been spending their summers here—on the world's largest uninhabited island—for one reason: Devon Island is, in just about every way imaginable, Mars on Earth.

"We're here," says Lee, the polar winds battering his unkempt jet-black hair,"because it is godforsaken."

What started out as Lee and a trio of gritty space freaks with a tent, a guard dog, and a loaded 12-gauge shotgun for fending off polar bears has grown into a full-scale international research station, the Haughton-Mars Project (HMP), with a million-dollar annual budget and dozens of participants. Lee acts as director. It's tempting to dismiss the project's work as an elaborate form of Martian make-believe. But within the past few years, the prospect of a manned mission to Mars has gone from being the closet desire of Red Planet visionaries to being an actual White House directive—with President Bush giving NASA a surprise budget bump to fund interplanetary exploration. This past summer the Phoenix lander, a spacecraft launched by NASA in 2007, confirmed the presence of potentially life-harboring water ice just beneath the Martian surface—and as China matures into a superpower, a second space race might be emerging, with Mars as the ultimate destination. Considering that cost estimates for a manned Mars mission are upwards of $1 trillion, Lee and his colleagues find themselves at the vanguard of an international endeavor that has a price tag comparable to what the Pentagon budgeted for the war in Iraq.

With a face full of stubble and a blue jacket decked in NASA patches, Lee slips on a backpack loaded with $25,000 worth of GPS gear and prepares for a traverse to test the equipment. A few scientists clack away at their laptops and make last-minute notes before he sets off across the ridge. If the movement to get mankind to the Red Planet—and it is a movement—has an epicenter, Devon Island is it. And inasmuch as our notions of paradise are aligned with our personal desires, to Lee and his colleagues this wasteland is Eden.

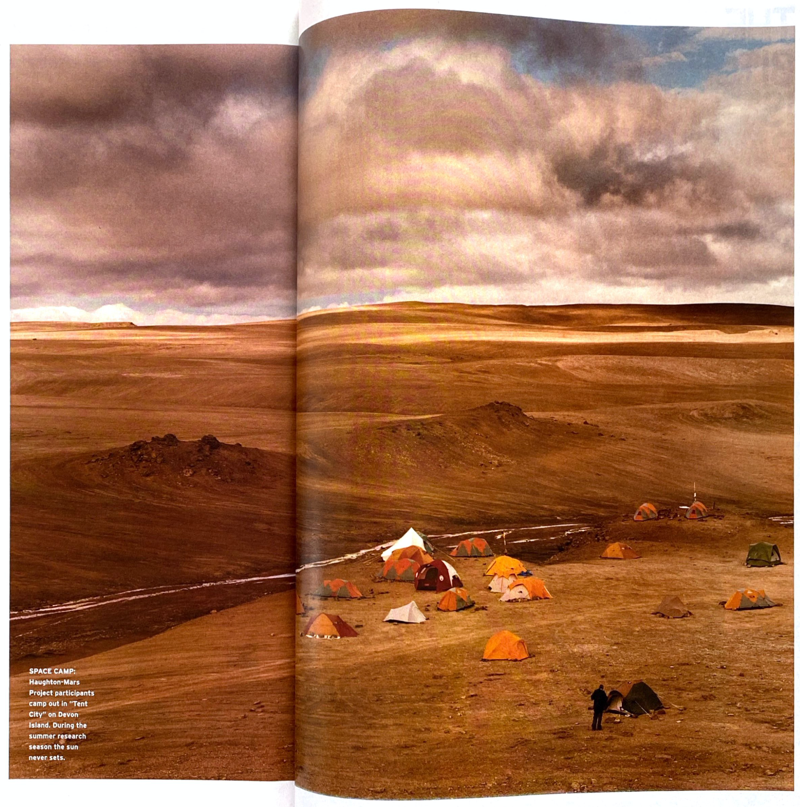

HMP IS A CLUSTER OF WHITE QUONSET-HUT TENTS LAID OUT IN A spoke formation over the Devon Island tundra. At this latitude the sun doesn't set all summer, giving the place the haunted air of a desert colony at “night,” when the only sound is the howl of the turbines by the Arthur Clarke Mars Greenhouse. But during the day the camp buzzes with activity. Scientists tear off on Suzuki ATVs to do fieldwork and amble in and out of the mess tent. Lee goes around the table every morning to hear everyone's plans for the day and checks up on what they've accomplished every night. There are geology tests, manned-rover simulations with ground-control support, and long treks in mock-up space suits around the canyons and rock piles. Lee is prone to remarks such as “The data is beautiful” and “All-righty-righty.” Ordinarily in the evenings—after a chef prepares dinner for the project's two dozen or so participants—they linger among the NASA banners and Martian globes for PowerPoint presentations on topics ranging from pressurized moon rovers to beryllium spectrometers.

But tonight is movie night, and Elaine Walker, the camp's education and outreach director, has something special in store: a music video she's made called “Martians.” The video features Walker in a fishbowl space helmet and a Jetsons getup with a miniskirt, doing a kind of intergalactic shimmy-shimmy around Devon Island. Little renderings of futuristic space colonies pop up behind her. “We are meant to be space faaaaaring.” she sings. “Mars is caaaalling me.” Everyone looks a little stunned.

“Cool,” is all Lee is able to muster.

Then HMP's chief field engineer cues up the main event, the 1964 classic Robinson Crusoe on Mars, starring Adam West and a monkey named Mona.

There is a lot of snickering and forehead slapping from the scientists at the barrage of mistaken Red Planet assumptions—among them: It's hot, the air is thin but breathable, and if mankind ever did make it there, we would almost cetainly bring along a chimp. A few people trickle out early to retire for the night as the sun continues its stubborn path around Devon's horizon.

“Up here on Mars,” says Commander Christopher “Kit” Draper, the film's dashing astronaut hero, into his recorder device, “you gotta face the reality of being alone forever.”

THIS YEAR, HMP'S PARTICIPANTS WEAR LITTLE BLACK WRISTBAND COMPUTERS that keep track of the amount of sun light they're exposed to and the amount of sleep they get. They have their reaction times tested nightly, and they must slog through a binder full of survey questions about their experiences on the island. It's all part of a comprehensive behavioral-health study being administered by Pam Baskin, a cheery middle-aged blonde who does contract work for NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

“You watch,” says Baskin, sipping a mug of steaming coffee in the mess tent one night. “The way the whole alpha-and-beta dynamic plays out here is fascinating.”

NASA, she says, is using the information to figure out how to build better astronaut teams. Baskin's other gig is at a project called NEEMO, off the coast of Key Largo, Florida, where astronauts spend weeks at a time in a submersible bolted to the ocean floor 65 feet below the surface as NASA observes their habits on video cameras. She's also gearing up for something unprecedented: Some time over the next two years, Baskin says, NASA hopes to send a team of astronauts to spend the entire winter in a confined research station in Antarctica.

There is nothing sci-fi about the preternatural and potentially deadly loneliness a human mission to Mars would inevitably entail. At its nearest approach, the Red Planet is still more than 34 million miles away. The shortest feasible time frame for a round-trip visit is about two and a half years. Isolation of that magnitude simply hasn't been studied in the context of a space mission. The closest precedent was Biosphere 2, the 1991 project in which eight people spent two years in a sealed glass ecological system in the Arizona desert. It did not end well. The team came out as two seething factions that don't talk to each other to this day.

“For a mission to Mars this is going to be a major issue, because people really do go sort of mad,” says Jayne Poynter, an author and environmentalist who was part of the Biosphere 2 crew. “The people generally attracted to going to Mars, or locking themselves up in a giant terrarium for two years, are people who think they're impervious. But the definition of the right stuff needs to change a little. It's not 'I don't crack up.' It's 'I can deal with it.'”

Even in the comparatively short duration of a Devon Island summer, some fissures have appeared at HMP. The most notable example, says Brian Glass, a NASA engineer who's entering his 11th season at the camp, came six years ago, when a student intern was "aggressively sharpening a bowie knife" in very close and apparently deliberate proximity to another participant.

THE MORNING AFTER THE MOVIE, LEE CALLS A MEETING TO PLAN the day's mission. He is hunched over a table stacked with frayed charts and satellite surveys of the island. Two teams will follow waypoints along two different routes across the island, gathering data for NASA to apply to lunar and Martian rover trips in the future, then rendezvous at a spot several kilometers north of the camp. Baskin's observations about the alpha/beta divide turn out to be spot-on: Lee will be leading the “A-team,” piloting the big orange Humvee with HMP's 28-year-old project manager, Nick Wilkinson, in the passenger seat; the “B-team” will be taking the “Mule”—a little red utility vehicle that looks like a military-issue golf cart. Each team will be followed by a caravan of ATVs carrying food, spare tires, and a pair of shotguns.

We set off across the tundra at 9:30 A.M., threading a long double line through the slate-gray silt. On two occasions, we stop for “EVA” (astronaut-speak for “extravehicular activity”) and Lee and Wilkinson exit the orange Humvee to do some simulated exploring.

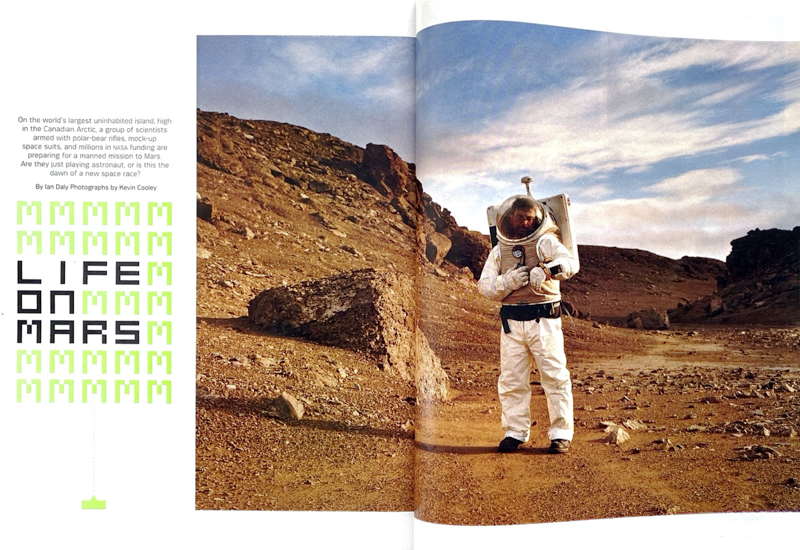

There is something spiritual about the act of putting on a space suit. The recipient must kneel before two assistants, hands stretched toward the sky, as though receiving some kind of cosmic communion. Tom Chase, a ruddy-faced engineer from the space-suit company Hamilton-Sundstrand, and Jesse Weaver, an 18-year-old ATV mechanic from rural Tennessee, team up to slide the big white sheath over Lee's torso before moving on to Wilkinson. Then Lee and Wilkinson head across the brittle scree to collect rock samples in little white bags and photograph the surrounding landscape. Wilkinson uses a garden hoe to scrape at random places in the rubble, pretending to search for soil samples, as Chase follows the duo with a handheld video camera. “Absolutely stunning EVA,” he narrates.

Lee lumbers over, his face completely obscured by the mirrored anti-glare bubble of his helmet. “This,” he says, in a voice that sounds buried underground, “is the definition of surreal.”

As there are only two space suits, the B-team has to go without. Their orders are to stay put for 15 minutes—to simulate the time it would take to put on the suits—and then proceed with their own EVA.

Since the sight of a couple of guys traipsing around Earth in space suits (or in the B-team's case, in imaginary ones) can come across as a little ridiculous, Lee is careful to point out that all of these measures are necessary elements of the “sim.” The value of their work on Devon Island is in its similarity to an eventual Mars mission, which is to say, it's messy. This is not some climate-controlled laboratory in Houston. Things break here. Weaver is constantly being sidelined by ATV tires punctured by the jagged terrain, cussing in his camo hat as he jabs tar strips into the knobby rubber. When one ATV breaks down six miles from camp, Lee gets out of the Humvee and tries to pull-start it. But it's no use. It has to be towed all the way home.

“Most of the people here are aware of the scorn or criticism peers give them for 'playing Mars,'” Lee says. “But the truth is it takes courage to do that. There will be critics who tell you it's not worth doing. Next thing you know, they're writing proposals to come here.”

But while the research is certainly real—along with the appeal of conducting it in what is essentially a self-governed scientific commune in the wilds of the High Arctic—an undeniable B-movie aesthetic permeates the scene. The space suits, though provided by the company that outfitted Apollo astronauts, are obvious low-budget prototypes. Real ones would weigh close to 200 pounds and cost upwards of $5 million each. Apart from the Mule and the Humvee, there's nothing resembling an actual rover. Even the scientists them selves are stand-ins: As it's not likely they'll be the ones making the journey to the Red Planet—if and when it happens—this is their Mars. It's hard to fault them for embellishing their role-playing with a few extra realistic touches. One scientist in a previous field season apparently took to riding around in pink-tinted ski goggles to make the landscape appear more Martian. And back in the Humvee, where Wilkinson tracks our meandering return trip to base on a MacBook, the satellite-rendered terrain on the screen seems suspiciously redder than what appears through the windshield. Since Wilkinson himself wrote the software, I ask if he took any liberties with the color of the satellite images. He shrugs his shoulders and grins.

“Maybe,” he says.

SPACE EXPLORATION HAS LANGUISHED SINCE THE DAYS OF APOLLO: most of NASA's dwindling slice of the federal budget is devoted to shuttle trips for the purposes of repairing satellites and ferrying supplies to the International Space Station. But on January 14, 2004, almost a year after the Coumbia space shuttle disaster, President Bush did something that confused a lot of people: He proposed a $12 billion budget increase for NASA over the next five years and a 16-year goal for getting humans back to the moon and then on to the Red Planet. “With the experience and knowledge gained on the moon, we will then be ready to take the next steps of space exploration: human missions to Mars and to worlds beyond,” he said.

For the finger-tapping daydreamers at NASA, it was the sign they'd been hoping for their whole lives. “NASA was just waiting for even a murmured consent,” says Dr. Horton Newsom, a scientist at the institute of Meteorics at the University of New Mexico, who's stirring a late night coffee in HMP's mess tent (NASA is funding his visit). “And they jumped at it—whether Bush meant it or not. That's what happened here [on Devon Island]. These people have been thinking about this for a very long time. But there was no funding available. The thing that's neat is what's being tested here now is mainline NASA projects and customs.” Nothing reflects that shift in official attitudes more than HMP.

“This polar station is dedicated to exploring other planets. It's the only one in the world,” says Lee from the driver's seat of the orange Humvee. “I'm living in a dream here.” That night in the Humvee, Lee confides something to me: He is dating Walker, the camp's outreach director and star of the “Martians” video. But the two sleep in separate tents to keep things professional. Lee's never been married—and while he has nothing but affection for Walker, his plans for her are far from nuptial.

“She deserves to be happy,” he says. "But I can't be tied.”

HIGH ON A RIDGE ABOVE THE HMP CAMP THERE IS A GIANT WHITE CYLINDER where a far different kind of Mars research is conducted. HMP participants generally avoid the site. It has, in a way, become a symbol of what happens when two strong wills—in this case Lee's and a former colleague's—collide. It is a reminder that confined, desolate places with few inhabitants generate schisms as well as fraternity. It is a place known simply as the Hab.

Ten years ago, Lee cofounded a nonprofit space-advocacy group called the Mars Society with a man named Robert Zubrin, an engineer and author. The goal was to get humans to Mars as soon as possible, bolstering NASA funding with private capital. Their first major project was to build a self-contained habitat that could accommodate a crew of six and simulate what living conditions in a Red Planet colony would be like—essentially Real World: Mars. They raised the money and contracted the U.S. Marines to parachute the construction materials onto Devon Island from a C-130 Hercules plane. But one of the parachutes detached from its cargo, which went into a free fall, shattering a crane, a trailer, and the pieces of what would have been the Hab's fiberglass floor. The entire construction crew walked off the job. Zubrin still managed to get the thing built, and Lee ended up commanding the Hab's inaugural six-person crew. But the ensuing scuffle over the cost and direction of the project resulted in so much acrimony that the two communicate only through a third party now. Lee has severed all ties with the Mars Society, and the two projects no longer share any formal connection.

“First of all, the main purpose of HMP has been geological re-search,” Zubrin says by phone from Colorado. “And that's fine, but that's not what we're doing. What we're doing is studying the exploration process itself.”

Lee's commentary is a little more biting.

“The Discovery Channel films what we are doing,” he says, “because those guys are just running around playing astronaut in there.”

The Hab crews have been making their way to Devon Island over the years to carry out their Mars-mission scenarios in quiet isolation, less than a kilometer away from Lee's camp below. Last year, they set a new record and spent four continuous months in the tin can—forbidden to leave unless wearing their space suits. Zubrin checked in on them remotely. He also, according to Glass, discouraged them from having any contact with HMP's participants.

“It's sad,” Glass says one freezing afternoon, gazing up at the Hab's looming white profile. “You get two isolated groups on what's otherwise the largest uninhabited island in the world—tiny outposts with just a few humans each—and what do they do? They form factions, glare at each other from across the runway, and refuse to talk to each other. In so many ways, this is typical of the human species.”

IN COSMOLOGY, THERE IS SOMETHING CALLED THE DRAKE EQUATION. It is not difficult to grasp. Essentially, it takes a stab at the number of stars in the galaxy, throws in the chances that some of these stars might have habitable planets and intelligent life, and spits out a number (N) that represents how many civilizations there are in our galaxy (including our own) that might be able to be contacted. The thinking in the sixties and seventies, when Apollo landings and Voyager probes fueled fantasies about our not being “alone out there,” was that the number was huge. “Somewhere on the order of a hundred thousand,” Lee says. But there was a troubling problem. Where were they? If our notion of the typical Mars-exploration advocate is someone who geeks out over the possibility of infinite worlds, Lee falls mysteriously outside of those bounds. It is not some Sagan-esque notion of contact that drives his ambitions. The way he figures it, the most likely candidate for N is 1—as in nobody (at least nobody at any bridgeable distance) is out there. “Well, for me, that's not disappointing,” he says. “That's fascinating. It gives us a profound sense of our loneliness. It makes everything we do special. We are it.”

His colleagues may dream of “terraforming” Mars—making it more like Earth—but Lee is repulsed by the idea. In that sense, the easy parallels between people like Lee and early maritime explorers fall short. Had those seekers glimpsed their New World before setting sail, only to see a frozen wasteland—inhabited by nothing, on the way to nowhere in particular—would they still have made the trip? Looking out through the dusty windshield of the Humvee, as the midnight sun clings to Devon Island's empty horizon, another comparison seems closer to the truth: Lee is not a modern-day Columbus in search of colonial glory. He is a modern-day Ahab pursuing his Moby-Dick.

“My personal interest is the unknown—it's what's over the hill,” he says. “Once people start arriving—once it becomes someone else's… turf… I want to move on. Maybe to Jupiter.”