The Out-of-Scope Request and Mr. Spock

How to avoid pouring gasoline on a fire.

Generally, a client’s out-of-scope request seems ridiculous because, as a project manager, you see these requests for what they often are—an attempt to get something for nothing. But clients don’t see things through your eyes, and PMs often don’t take the time to understand where the client is coming from, either—clients generally care a lot about their project and they’ve paid money (maybe a lot, for them) for you to solve a problem. They just want things to turn out right.

Or, maybe they’re an asshole.

Regardless, an out-of-scope request is a potentially volatile situation that’s wrapped in a thick layer of emotion and mis-matched expectations. But instead of seeing this as a conflict to avoid, or an argument to win, what you’ve really been presented with is an opportunity to strengthen the relationship with your client. Easier said than done.

What to feel when you’re feeling feelings

Once you have what you suspect is an out-of-scope request in writing and you’ve talked the situation over with your team, it’s time to put some careful consideration into your response. But it’s hard to strike a constructive tone and keep your cool when you’re essentially having to convert an illogical request into a logical course of action.

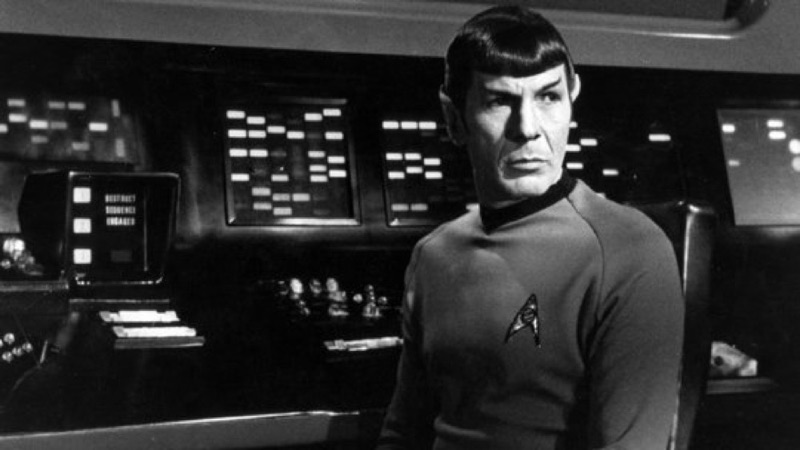

When I’m in this situation, to cut through all the non-essential stuff that I feel and get to the stuff that I know, I pretend I’m writing to Spock from Star Trek. Spock may be the polar opposite of the client I’m working with, but I operate on the assumption that most generally reasonable people have a hard time rejecting reason. Even if that assumption is false, since this response will be the first volley in what has the potential to become a heated discussion, I don’t want to start things off by pouring gasoline on what might turn into a fire.

How do you win over a Vulcan? By being clear, concise, patient, firm, and sensible. Spock doesn’t care about the project’s emotional baggage or extenuating circumstances. He doesn’t care about the timing of the request, how that unexpected bug is already threatening the schedule, or how hard everyone’s been working on the project. Spock cares about a logical argument based on facts and coming to an equitable solution.

If I can’t hear Leonard Nimoy’s voice when reading over my response, I rewrite. I don’t hit ‘send’ until I’m confident I’ve built a succinct, logical argument supporting my view that the request is out of scope, and suggesting an alternative course of action to keep the process moving forward.

Are you out of your Vulcan mind?

The one thing your client won’t do upon reading your response is congratulate you on your astute use of logic in diffusing a particularly sticky situation. More likely, they’ll be shocked and maybe even angry that you’re pushing back on their request. But the response wasn’t the end of the process, it was the beginning.

A well thought-out response gives both you and the client an opportunity to find that point in the past where you both shared a common understanding, and identify where that understanding started to diverge. This shouldn’t be about about who’s right and who’s wrong, or about backing down versus drawing a line in the sand. It’s about working together, respectfully.

"May I say that I have not thoroughly enjoyed serving with humans? I find their illogic and foolish emotions a constant irritant."—Spock, “Day of the Dove”

Projects would be easy to manage if it wasn’t for all the humans.